Cyber warfare has been on my mind for a few weeks, even before the WannaCryptor incident. It’s been there because I’ve been looking at the innovation context for a digital service I’ve been designing as part of my T317 end of module project. That service is for government, and one of the risks is that someone will try to attack or subvert it.

The other thing that has brought cyber warfare to my head is the forthcoming general election in the UK. There are signs that both the UK referendum on the EU and the US election night have been affected by cyber warfare.

What is Cyber Warfare?

The popular view is hackers in a basement tracking people, bringing down other computer networks and stealing money. They do impossible things with a few clicks of the keyboard. Taking over CCTV cameras, planting data, or stealing it. The black hat guys use viruses, phishing and social engineering to empty your bank accounts and steal your life.

Personally I don’t buy that image. Bits of it certainly happen. There are a whole load of criminals out there looking to make a profit out of people. But it isn’t as easy or as glamourous as TV would have us believe.

Cyber isn’t Warfare

I see Cyber as a buzzword. It isn’t a new phenomenon. Like a lot of other things it has become much easier to do at scale with the spread of the internet. Warfare is the domain of the military, and implies state sponsored violence from at least one of the parties. Even in small insurgencies the insurgents are acting for political reasons in what they see as their national interest. As that famous Dead Prussian Carl von Clausewitz put it, war is the continuation of politics with other means. So for something to be defined as warfare there needs to be some sort of political dimension to it.

Cyber on the other hand is more of a police and intelligence services matter. Sure, malicious effects on certain systems can cause deaths and injuries. However it’s more about information and criminality than state sponsored violence or politics. There are daily cyber incidents, and they are almost all criminal in intent.

As I see it Cyber has the following potential components

- Defence against threats (as multi-pronged as the threat landscape)

- Information operations to persuade people to a point of view (AKA propaganda)

- Intelligence gathering, both passive and active

- Disruption of physical infrastructure – e.g. stuxnet style attacks, also control of things attached to the internet (IoT is scary)

- Facilitation of criminality, whether stealing data/money or supplying contraband or illicit goods or services online

WannaCryptor Wasn’t Warfare

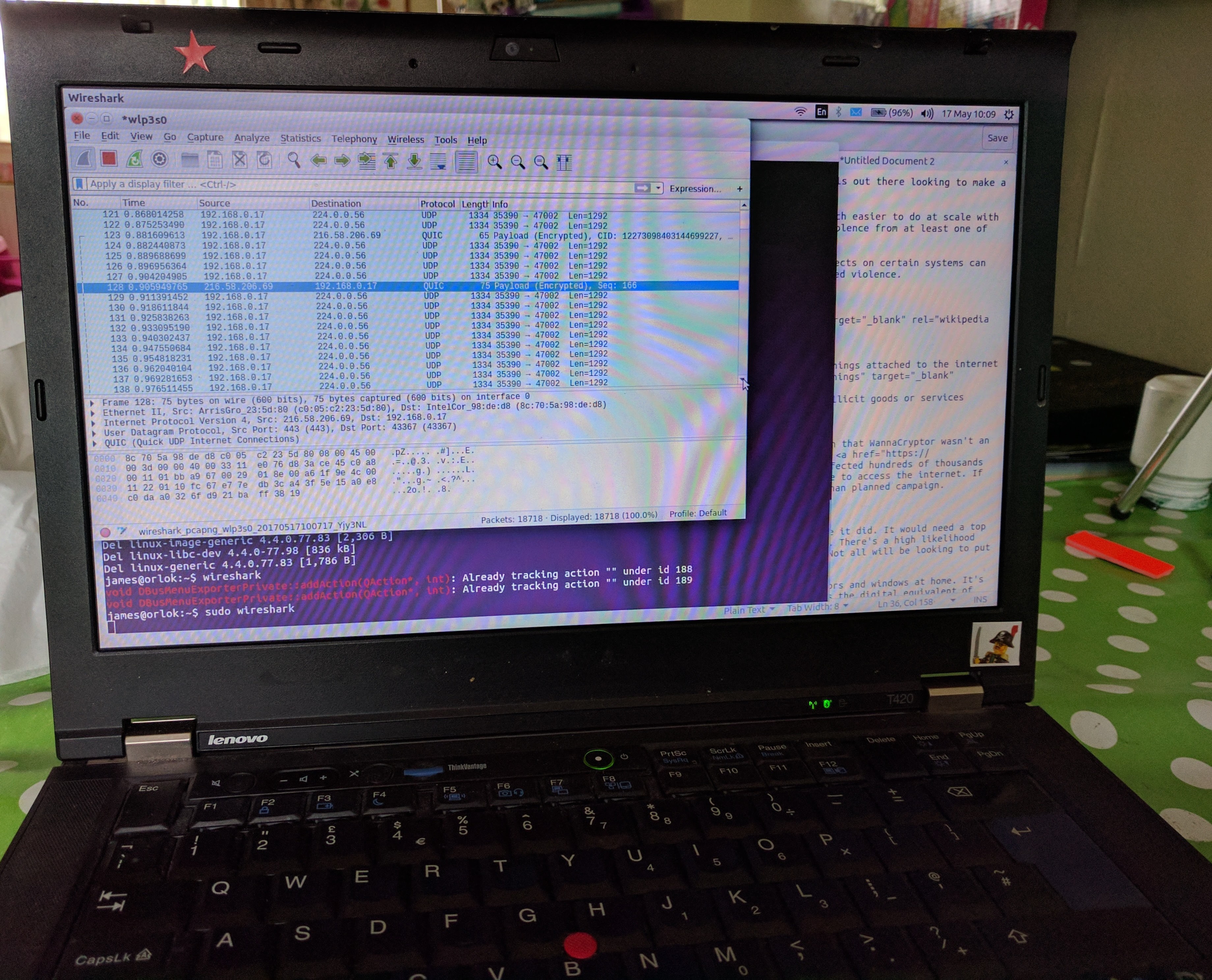

While the details aren’t entirely clear on this incident I think there’s enough data to be certain that WannaCryptor wasn’t an attempt at cyber warfare. I’m pretty sure about that because both of the sheer scale of the infection and the ransomware payload. If it had been political then it woul have been more closely targetted, and there would have been a message attached to it (other than give me some bitcoin). WannaCryptor infected hundreds of thousands of machines across 150 countries. That’s pretty much all countries developed enough to be able to access the internet. If you watch the video of the spread it goes round the world with office hours. It’s more Pandemic than planned campaign.

There’s an outside chance it was planned, but I doubt that it was intended to operate at the scale it did. It would need a top level authority to create that level of impact to deflect suspicion from it being state sponsored. There’s a high likelihood that several affected states will be putting significant effort into tracking down the culprits. Not all will be looking to put them in front of a court.

Cyber Defence

This is an area that should really be in our own hands, in much the same way that we close our doors and windows at home. It’s down to all of us to recognise the threats and act to prevent them. Clicking on links in emails is the digital equivalent of flashing a wallet in a dodgy part of town. Sensible people just don’t do that.

The secret of Cyber, or Digital, or IT, or computers, is simply that they are communication devices. Anyone can talk to anyone else directly. There’s no border, no internal policing, nothing to stop a dodgy person directly contacting you. So everything needs defending directly. (See Castles in the Sky for my poem about security in the cloud). Every moment of every day carries the risk of compromise. Cyber is like a permanent counterinsurgency, except with viruses, phishing and social engineering in place of IEDs, ambushes and informers.

Cyber as a buzzword

I’ve claimed there’s no such thing as cyber warfare. There are parallels with real warfare though, and cyber operations can, and do, support military campaigns. That doesn’t make it a military thing though. Civilians and intelligence services support military campaigns too. There’s probably also a need for a civilian equivalent of the reserves for the cyber security people, whether defensive or offensive.

Security is millennia old. IT security is decades old. Cyber is simply the latest buzzword to make it sound sexy and attract funding. That’s a good thing, because it can affect us all directly and indirectly. So we all need to pay it some heed.

Security isn’t hard. It just needs you to think about it, and ask questions. Most importantly, don’t let the fear grip you. Fear makes us react irrationally.

My ‘cyber’ credentials

There are a lot of instant cyber experts out there. I’m not one of them. I’ve been working for the UK government in IT related roles back to 1995. This has included being part of the Departmental IT Security Committee when we did Y2K and being on the forefront of designing and building secure digital systems for part of the UK Home Office. I’m a professional member of the British Computer Society. There’s a lot about IT security that I don’t know, I look to the experts I work with on that, but I definitely know more than most of the media pundits you’ll have read recently.