We’ve had a succession of changes in socially acceptable behaviour. First we couldn’t smoke on trains, then it was smelly food, noisy headphones and excessive alcohol consumption. Now there is the most sensible change in social responsibility. The Daily Fail is now not allowed on Britain’s rail network. About time if you ask me…

All posts by james

Poetry – Bloom by James Kemp

Bloom

“Splash!â€

A roar over my head closes

from behind and drowns the radio.

Binoculars brought to bear, I observe

the seed embedding. It grows

a small orange blossom. Morphing

into a larger, darker flower

climbing from the point of impact.

Rain patters over the iron roof

as sods and stones strike sonorously.

The flower is gone, dissipated

in a cloud of dust, and silence

returns.

Notes

This was the first full poem that I wrote, and this is the fourth draft, which may not be the final version. It was prompted from the memory of watching artillery shells burst when training as an artillery forward observer at Warcop training area in Cumbria in 1991. On the FOO course I gave an incorrect map reference and the first ranging shell burst about 150m in front of me (the wartime safety distance is 250m, in peacetime double that). Normally you don’t see the orange flame of a bursting shell, I only saw it for an instant, and that most likely because of how close I was to the impact point. By chance the shell landed right in the centre of the field of vision of my binoculars. Needless to say this event was accompanied by copious swearing as I ducked back down inside the trench. That was followed by “Add one thousand, repeat.”

As part of my drafting process I read out the poem on video camera, so you can watch/listen to it as well as read it.

<iframe src=”//www.youtube.com/embed/1hsOw80cs-U” height=”315″ width=”560″ allowfullscreen=”” frameborder=”0″>

Related articles

Book Review – Flames in the Field by Rita Kramer

Flames in the Field: Story of Four SOE Agents in Occupied France by Rita Kramer

Flames in the Field: Story of Four SOE Agents in Occupied France by Rita Kramer

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

While this has lots of fascinating information about SOE Operations in France in WW2 it needs a better editor. The nature of the story, primarily of the secret operations in German occupied France in 1943 and the SD penetration of the SOE network, is one of many parallel threads and the uncovering of a mystery. So this makes it hard to just write a linear narrative, and the author has done a pretty good job of writing very readable prose that clearly explains what is going on. However there are a few places where the ordering of the material goes backwards within a few paragraphs and crucial pieces of information are given out of order.

The book shows an awful lot of research was done by the author, over a period of what seems to be years, and building on the work done by a number of predecessors. There is an academic level of referencing and footnotes. Â There are several distinct parts to the book. The first is a narrative on four women SOE agents killed by the nazis at Natzweiler, which then widens to encompass the others that were arrested around the same time and that shared their captivity in Fresnes and then Karlsruhe. Each of these women is identified and has their life story before joining SOE told. Where it is known this then leads up to how they were captured.

Another piece of the narrative are the attempts by others (initally Vera Atkins in 1945-6 and then Jean Overton Fuller) to find out what happened to the women after they were arrested. This then leads nicely into attempts to work out whether or not the women were betrayed, and if so by whom. There has been a lot of controversy about this, and many of the participants in the events have competing theories. Traitors in SOE, strategic deception and sacrifice by the British, french informers, poor operational security of the SOE agents, German counter-intelligence competence. Each of these is disected in turn, sometimes adding new perspectives to help rule them in/out.

Lastly there is some discussion of the post-war discoveries as the secrets kept for 20-30 years following the war started to come out. How the revelations around both Ultra intelligence and the British strategic deception plans changed how the events of 1943 are interpreted to modern eyes.

On a content basis this should be a five star book, it draws together all the earlier sources and is well written. However the structure lets it down, and makes it harder to assimilate. It reads like the collected notes of the author more than as a structured narrative.

Related articles

Book Review – First Light by Geoffrey Wellum

First Light by Geoffrey Wellum

First Light by Geoffrey Wellum

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

If you want to know what it was like as a spitfire pilot in the Battle of Britain, then this is the book you need to read. The author was a public schoolboy that joined the RAF just before the outbreak of war. He signed up in the spring of 1939 and started training as soon as he finished school in July 1939.

The first third of the book is a very detailed account of his entry to the service and the flight training. Through this we get to know the author as a typical public schoolboy, he struggles with the academic side, but has no problems with the discipline and dealing with being in a service institution. Flying is clearly his passion, and is most of the focus of the book. Other than his struggles with the training matter, and the mental stress of combat flying and dealing with the progressive loss of his friends there is little else in the story.

There is no bigger picture, or even narrative of the wider progress of the war to put things in context. When he is rushed out of training and posted directly to an operational squadron (no.92) it is because the Germans have invaded France, however we’re not directly told this. The closest he comes is when the rest of the squadron patrol over Dunkirk, losing many of the old hands including the CO Roger Bushell (who lead the Great Escape). If you didn’t know how the war went then you could be baffled by some of this. Also, there is nothing about the Battle of Britain directly, other than accounts of some of his more notable sorties (the first, some where he has narrow escapes or shoots down or damages enemy aircraft).

That said, it is a very good first hand account of what it was like on a very personal level. The flights are very well described in some detail. It is clear that Geoffrey Wellum was deeply affected by his war experience and that being an operational fighter pilot represented the pinnacle for him. His tour as an instructor between operational tours is dispensed with in a couple of pages. The narrative between flights shows him moving from an enthusiastic schoolboy to a novice pilot and eventually to a mentally exhausted veteran.

Related articles

Game Design Notes: World War One Strategic Battles

This was originally written as a game design session prompt for a session at Chestnut Lodge Wargames Group back in April 2004. A discussion thread on about this excellent blog post http://sketchinggamedesigns.blogspot.com.es/2014/01/the-wrinkles-of-tactics-first-world-war.html lead me to dig it out and post it here.

World War One Strategic Battles

Turn structure

Three turns per year, March – June (Spring), July to September (Summer) and October to February (Winter).

Actions

Small offensives can be prepared and launched within one turn. Large offensives take a turn of preparation and then take a whole turn of offensive action. Small offensives can be carried on into large offensives.

Battles are fought in phases.

- Preparation: divisions are allocated to the line, first wave, second wave, exploitation, training and reserve tasks

- Bombardment

- Assault

- Counter-attack

- Continuation phases if appropriate

Resolution

Fighting is resolved at Army level, with Divisions as the smallest unit (two down). One player per Army?

Three kinds of Division:

- infantry (standard)

- cavalry (rare)

- artillery (representing Corps/Army artillery)

All divisions of a particular kind are the same except for level of experience and training. This can be open to the player as it was generally well known which units were the most effective and had the most offensive spirit.

Special training can be given to units to allow them to be competent at tasks, e.g. building fortifications, pioneer tasks, tank support, amphibious landings etc. The number of turns that they get in this task should be recorded separately from that of infantry training.

Infantry divisions take one turn to raise, cavalry and artillery take two turns. Ideally more training should be given before a unit is used in combat. A minimum of three turns of training is suggested before committing a new Division to the assault.

Training States Turns Experience

New 0 none

Effective 2 time in line

Regular 4 time in line

Experienced 6 time in major offensive (including defending)

Veteran 8 Several major offensives

Both the number of turns training and the combat experience are required for the troops to be considered at the higher training state. Note that the training state is just a label and not a guarantee of performance.

Political End

Resource allocation

Sources of resources

Taxation – can set a proportion of GDP to be spent on government. Level has effect on popularity, standard of living, economic growth, industrial output.

Loans – need to be repaid later but avoids some of the problems with increasing taxation. Can also inject foreign capital into paying for the war which increases overall resources available to any particular nation.

Manpower

Can conscript or get volunteers. Quality issues with conscription but increased numbers may offset that. Volunteers make more aggressive units, conscripts more passive ones. Has impact on economic growth, popularity & industrial output. Also issue of women’s rights if they are mobilised for the war effort.

Related articles

The Stress of Battle – Pt5 Operational Research on WW2 Heroism

This is the fifth and final part of my extended review of The Stress of Battle by David Rowland. It is such a strong piece of operational research on WW2 heroism that I thought that it would be useful for wargame designers (and players) to understand what the research evidence is for what went on in WW2 battles. This part is on the effects of heroism and combat degradation.

Combat Degradation

Combat degradation is a measure of how less effective weapon systems and individual soldiers are in actual combat when compared to training exercises and range work. A score of 1.0 is equivalent to not being degraded at all. Degradation to 0.3 would mean that it was operating at 30% of its peacetime range effectiveness.

- the analysis by Rowland’s team broadly matches that done by Wigram in 1943, that there are three classes of effectiveness.

- About 20% of those involved could be classed as heroes (26% for guns, 9% for tanks).

- Of the rest, one third were ineffective (either they didn’t engage, or what they did do didn’t have any significant impact) (27% of the total);

- The remaining two-thirds were about 30% effective (53% of the total);

- Weapon systems crewed with at least one hero were about five times more effective than those with no heroes;

- Overall effectiveness of a unit = 0.2+([Heroes/gun]*0.8)

- Leadership improves combat effectiveness (i.e. more officers/SNCOs present leads to greater effectiveness, which is the reason that tanks are less effective than gun crews).

Impact of Heroism

Rowland and his team compared the effectiveness of the most effective and the partly effective groups in both the historical battles for which there was information and also for the field trials conducted by the British Army in the 1970s & 1980s. What they found was that there was the same variability within the two groups, which was attributed to opportunities to engage. However there was a significant difference between the groups, which was attributed to heroes being more effective.

Rowland and his team compared the effectiveness of the most effective and the partly effective groups in both the historical battles for which there was information and also for the field trials conducted by the British Army in the 1970s & 1980s. What they found was that there was the same variability within the two groups, which was attributed to opportunities to engage. However there was a significant difference between the groups, which was attributed to heroes being more effective.

- Heroism seems to be a product of genetics, social conditioning and values. Many recipients of gallantry awards had previously been mentioned in despatches, or were decorated again.

- Comments on citations for subsequent decorations indicate that a second award always required a stronger case than the first award did.

- Heroes maintain their combat effectiveness in future battles, even if not further awarded.

- Heroism is more likely at higher ranks (i.e. officers and senior NCOs (Sergeants and above) are more likely to be in the higher performing groups than other ranks).

- Officers had 1.56 Awards/KIA

- SNCOs had 0.52 Awards/KIA

- Other Ranks had 0.10 Awards/KIA

- Rank may be an effect (promotion coming from heroic behaviour) or a cause (feeling responsible because of higher rank).

- Crews operate at the level of the highest effective person present.

Probabilities of Heroic Action being recognised

| Rank | ||

| Senior Officers | 30.00% | 34.00% |

| Lieutenants | 6.10% | 4.20% |

| All Officers |

14.00% |

14.00% |

| Sergeants & Warrant Officers | 6.10% | 8.40% |

| Corporals / Bombardiers | 2.50% | 2.95% |

| Privates & Equivalent | 0.48% | 0.73% |

NB there is a possibility that the awarding of decorations was unfairly skewed by rank, and that those of lower rank that performed heroically weren’t adequately recognised.

Gurkhas

Gurkha units were noticably different from British unit, and appear to be 60% more effective in inflicting casualties on the enemy and 60% more likely to be decorated. This comes at the price of higher levels of casualties.

Surprise & Shock

The defintion of Surprise is “the achievement of the unexpected in timing, place or direction such that the enemy cannot react properly”. This is distinct from Shock, where soldiers could react, but didn’t.

Again historical analysis was used and battles where surprise and shock were involved were identified. These were then compared with other battles with similar characteristics so that only either Shock or Surprise were different. The two factors being compared individually with a reference set.

Surprise

- Attack surprise reduces infantry defence effectiveness by 60% at 3:1 attack ratio.

- Attack surprise may vary with force ratio (being more marked at low ratios and less effective at higher ratios)

- Surprise for tank vs tank reduces casualties  by a factor of 3 at 1:1 attack ratio for the side achieving surprise.

- Attacks below 1:1 ratio were successful 65% of the time when surprise was achieved, where attacks at these ratios were never successful without surprise

- At force ratios above 1:1 surprise is less important to success, although there is still higher levels of success with surprise, just not statistically significant.

- with surprise force ratio is less important to success (at 1:1 70%, at 3:1 76%)

- without surprise the probability of success increases in proportion to the force ratio (at 1:1 40%, at 3:1 54%)

Shock

- Infantry attacks caused shock in about 15% of cases, rising to 50% when combined with surprise and some of the factors below. Three factors were found to have influenced the ability of infantry to inflict shock:

- Charge distance was usually under 100 metres (limited by weight of kit), where it was longer that was found to be because the enemy had already broken.

- Visibility was significant, typically shock occurs at night or in poor visibility including where the terrain offers concealment

- Defence morale was affected by Battle cries, cheers and yells seemed to put defenders off balance.

- Bayonets played a major role (but not to cause casualties, as a psychological weapon inducing the enemy to surrender or run away).

- Tank attacks caused shock in about 10% of battles analysed.

- ‘Invulnerable’ tanks cause shock which can lead to panic, in about 50% of cases

- Surprise alone caused shock in 27% of the time

- Surprise + invulnerable tanks gave 70% Shock

- Surprise + poor visibility gave 85% shock

- Surprise + all of the above gave 95% shock

- Air attacks cause shock most often when they are a dive/strafe attack where the aircraft is aimed directly at the target.

- Typically shock by ground attack reduces defence effectiveness by 65%.

Related articles

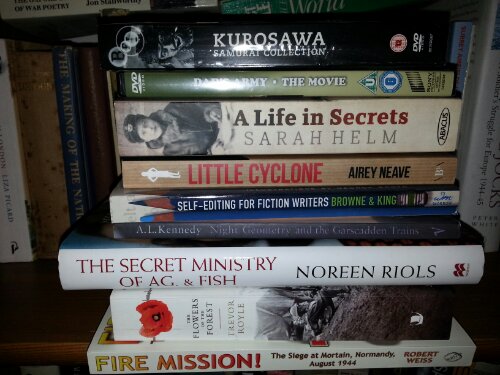

Christmas Reading

The Stress of Battle – Part 4 – Op Research on Anti-Tank Combat

This is the fourth part of my review of The stress of battle: quantifying human performance in combat by David Rowland, which is an essential piece of Operational Research on WW2 and Cold War combat operations. This part covers the findings on anti-tank combat.

Anti-Tank Combat

Unlike small arms, the effectiveness of weapons used for anti-tank combat has changed considerably over the course of the mid-20th century. From non-specialist gunfire in WW1, to high velocity armour piercing in WW2 and then to Anti-Tank Guided Weapons in the Cold War period. This makes the operational research on anti-tank combat harder to do because the start point needs to be battles where only one kind of AT weapon is in action. Much of the analysis on anti-tank combat starts with the ‘Snipe’ action during the second battle of El Alamein in North Africa where data on each of the guns individually was available.

- ‘heroic performance’ plays a large factor in the effectiveness of anti-tank guns

- about a quarter of guns (at most) performed heroically (including those where platoon, company or battalion level officers assisted with firing guns)

| Campaign / Battle | Heroes | Others | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. Guns in combat |

Total engagements |

Tanks Hit per target per gun engagement |

No. Guns in combat |

Total engagements |

Tanks Hit per target per gun engagement |

|

| Greece (1941) |

8 |

8 |

0.400 |

38 |

44 |

0.054 |

| Alamein (2RB at Snipe) |

10 |

25 |

0.150 |

23 |

27 |

0.048 |

| Medenine (Queens Bde) |

2 |

7 |

0.430 |

22 |

38 |

0.027 |

| Medenine (Guards & NZ) |

6 |

9 |

0.390 |

14 |

14 |

0.120 |

| Total all battles |

26 |

49 |

0.275 |

97 |

123 |

0.052 |

- Â rate of fire is proportionate to target availability (i.e. when there are multiple targets crews fire faster)

- the median point for heroes was 0.3 tank casualties per gun, where for non-heroes it was 0.03 tank casualties per gun

- tanks are less effective in defence than AT guns alone, or tanks supported by AT Guns

- AT Guns with tanks apparently kill three times more tanks than the tanks would on their own

- AT Gun performance is attributed to having a higher concentration of SNCOs and Officers with deployed ATG compared to tanks (about three times as many)

- heroes were disproportionately represented by SNCOs and Officers (at least in terms of who got the medals), in 75% of cases an SNCO or Officer senior to the gun crew commander was involved

- Paddy Griffith is quoted on tank casualties that “relatively few appeared to have been caused by enemy tanksâ€

Overall it shows that the biggest single effect in anti-tank combat was down to leadership. Where gun crews are well lead then they are significantly more effective in battle. This is assuming that the guns in question can have some effect on the tanks that they are shooting at, which was the case in all of the battles examined (including a mix where the guns defended successfully with those where the gun lines were overrun by tanks).

Concluded in Part 5 – Operational Research on Heroism, Shock & Surprise

Related articles

The Stress of Battle – Part 3 – Op Research on Terrain Effects

This is the third part of my extended review of The Stress of Battle by David Rowland. It is such a strong piece of operational research that I thought that it would be useful for wargame designers (and players) to understand what the research evidence is for what went on in WW2 battles.

Fighting in Woods

The data comes from an analysis of 120 battles that took place in woods or forests from the US Civil War to the Korean War. It also applied all the things from the previous research and tried to see how woods differed from combat in other types of terrain.

| Woods | Open | Urban | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attacker casualties per defence MG (at 1:1 force ratio) |

0.818 |

2.07 |

0.76 |

| Force Ratio Power Relationship |

0.418 |

0.685 |

0.50 |

- Defence is less effective in woods, most likely because limited fields of view mean that the engagement ranges are shorter

- Combat degradation is greater in woods during night battles

- Artillery suppression is less effective in woods (presumably because the trees absorb some of the shell splinters)

- Attack casualties reduce with attacker experience (after ten battles attacker casualties are half of that of inexperienced troops)

Continued in Part 4 – Operational Research on Anti-Tank Combat

Related articles

Stress of Battle – Part 2 – Op Research on Urban Battles

This is the second part of my review of The stress of battle: quantifying human performance in combat by David Rowland, which is an essential piece of Operational Research on WW2 and Cold War combat operations.

For this part I thought that I would focus on the lessons on urban battles. Rowland and his team used historical analysis on lots of WW2 urban battles and then compared this to a series of field trials using laser attachments to small arms and tank main armaments in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The approach was to find battles where single variables could be controlled, and then use them to work out what the effect of that variable was on outcomes.

Here’s an interesting table on how attacker casualties vary by odds and the density of defending machine guns. Interestingly, in successful assaults the defender casualties are constant.

| Force Ratio | Attack Force(100 man Inf Company in Defence) | Attack Casualties (killed and wounded) | Defence Casualties (Killed, POW & Wounded) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 MG / Section | 2 MG / Section | |||

|

1:1 |

Infantry Only |

16 |

24 |

80 |

|

3:1 |

Infantry Only |

27 |

40 |

80 |

|

1:1 |

Heavy Tank Support (no def AT) |

3 |

12 |

80 |

|

3:1 |

Heavy Tank Support (no def AT) |

5 |

20 |

80 |

|

1:1 |

Trained attack infantry only |

8 |

12 |

80 |

|

1:1 |

Trained attack Heavy AFV support |

2 |

6 |

80 |

The interesting thing for me is that training/experience counts for a lot, halving casualties. Also attacking with the conventional 3:1 odds for success increases the casualties that you suffer, without having any appreciable difference in those inflicted on the enemy (although it does make it more likely for successful attacks with untrained/inexperienced troops).

Adding armour support makes a huge difference too. Although tanks in urban areas are more vulnerable if they lose their infantry support. However with infantry they significantly reduce attacker casualties.

- Defence experience gave no detectable benefit to causing casualties, but attack experience does (in urban combat)

- typically three times as many defenders will surrender (some wounded) as are killed or withdraw, the only sensitivity on this is being completely surrounded (so 20% dead, 60% captured (incl wounded) and 20% withdraw);

- attack casualties are less affected by force ratio in urban attacks than in open countryside;

- successful defence of urban areas is best achieved by light defence with counter attacks supported by armour

Rubble & Prepared Defences

This another area covered. There is a general increase in attacker casualties by about 50% when defenders are in rubble or prepared defences. The primary effect of rubble though is to slow down rates of advance.

- Rubble halved the rate of advance compared to undamaged urban areas

- maximum unopposed advance rates were about 800 metres per hour in urban areas (400m/hr for rubble)

- Opposition slowed the advance by a factor of 7

An interesting aside on this was the relative effectiveness of different types of German Infantry. Parachute troops and Panzergrenadiers were reckoned to be tougher opponents than normal infantry. However the analysis showed that the extra stubbornness was a factor of the higher than normal allocation of MGs to those troops. The rate of attacker casualties per defence MG wasn’t significantly different.

Continued in Part 3 – Operational Research on Terrain Effects

Related articles