Category: History

-

![Destructive & Formidable by David Blackmore [Book Review]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/dsc_0068.jpg)

Destructive & Formidable by David Blackmore [Book Review]

Destructive and Formidable by David Blackmore is a quantitative look at British infantry doctrine using period sources from the British Civil Wars of the seventeenth century up to just before the Napoleonic wars. If anything you can see the constancy, which drove the success in battle of British forces, even when outnumbered. Development of British…

-

Washington Conference Megagame Newspaper Reports

For his 70th birthday Dave Boundy decided to run his Washington Conference Megagame again. It’s at least the fourth time Washington Conference has been run as a Megagame. I’ve previously played as a Japanese Admiral, although this time I was one of the press team. Also, unlike recent megagames the entire cast list were veteran…

-

Blood and Thunder 4 – a Megagame of Pirates

Alexander and I played arms merchants in the Blood and Thunder 4 pirate megagame on Saturday. It was mostly a fun game, although there were a couple of sticky points for us as merchants. I was cast as Theophilus Blodwell, a Glaswegian on the run from the British Authorities. As well as being an arms…

-

Divided Land – Being a Terrorist in a Megagame

I played the leader of a terrorist organisation in the Divided Land megagame. Divided Land was about the situation in Palestine in 1947, we played from March through to an agreement on partition in August 1947. We then made plans on what would happen when the agreement came into force at 00:01 on 1st January…

-

![Undeniable Victory – offside report [Megagame]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IMG_20171118_164040.jpg)

Undeniable Victory – offside report [Megagame]

Today I played in Undeniable Victory, Ben Moore’s megagame of the Iran Iraq War. I was an Iranian Radical and a member of the Council, starting off as the Procurement Minister responsible for buying military kit. Undeniable Victory I was a late entrant to Undeniable Victory, getting a place because someone else couldn’t make it.…

-

Dunkirk – A different sort of war movie

I went to see Dunkirk with my 11 year old son last week. I’d read some reviews beforehand and chose the IMAX version. It’s an amazing movie that I think will bear watching again. I’ll try to avoid spoilers. Dunkirk The movie focuses on three stories, one on Land (over a week), one on the…

-

Mass mobilisation for World War Three?

Mass mobilisation for a world war level conflict would need the country to repeat what it did for WW1 & WW2. Discussion I’ve read on twitter amongst those interested and knowledgable about defence (a mixture of serving officers, military historians and political observers) suggests that Britain has a real problem with the level of defence…

-

Leading Gurkhas – A Child At Arms by Patrick Davis [Book Review]

A Child at Arms by Patrick A. Davis My rating: 5 of 5 stars Davis became a Gurkha officers almost straight out of school in WW2. A Child At Arms should be on reading lists for junior officers and anyone involved in military policy. It compares well to Sydney Jary’s 18 Platoon, which was held…

-

![Dominion by C.J. Sansom [Book Review]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/350px-bundesarchiv_bild_183-h12751_godesberg_vorbereitung_munchener_abkommen.jpg)

Dominion by C.J. Sansom [Book Review]

Dominion by C.J. Sansom My rating: 4 of 5 stars I was recommended Dominion by a couple of friends after my review of the TV version of SS-GB. Dominion is a huge tome, it’s 700 pages long, and my first thought was that it probably needed some more editing. However I found it an easy…

-

SS-GB is Archer of the Yard a Collaborator?

Is Archer of the Yard just doing his civil police job or is he a Nazi collaborator? I have a fascination with the moral dilemma of being a collaborator or changing sides in civil wars and occupations. None more so than the situation that Archer of the Yard finds himself in with SS-GB. Let’s unpack…

-

![SS-GB [review] BBC Adaptation of Len Deighton’s SS-GB](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/SS-GB-image-Buck-Palace.jpg)

SS-GB [review] BBC Adaptation of Len Deighton’s SS-GB

I watched the BBC Adaptation of Len Deighton’s SS-GB last night. I read the book a long time ago, it was probably one of the first alternative histories that I ever read. I’ve also enjoyed Young Lions by Andrew Mackay which is also set post-German Invasion of Britain. SS-GB Review SS-GB has a lot of…

-

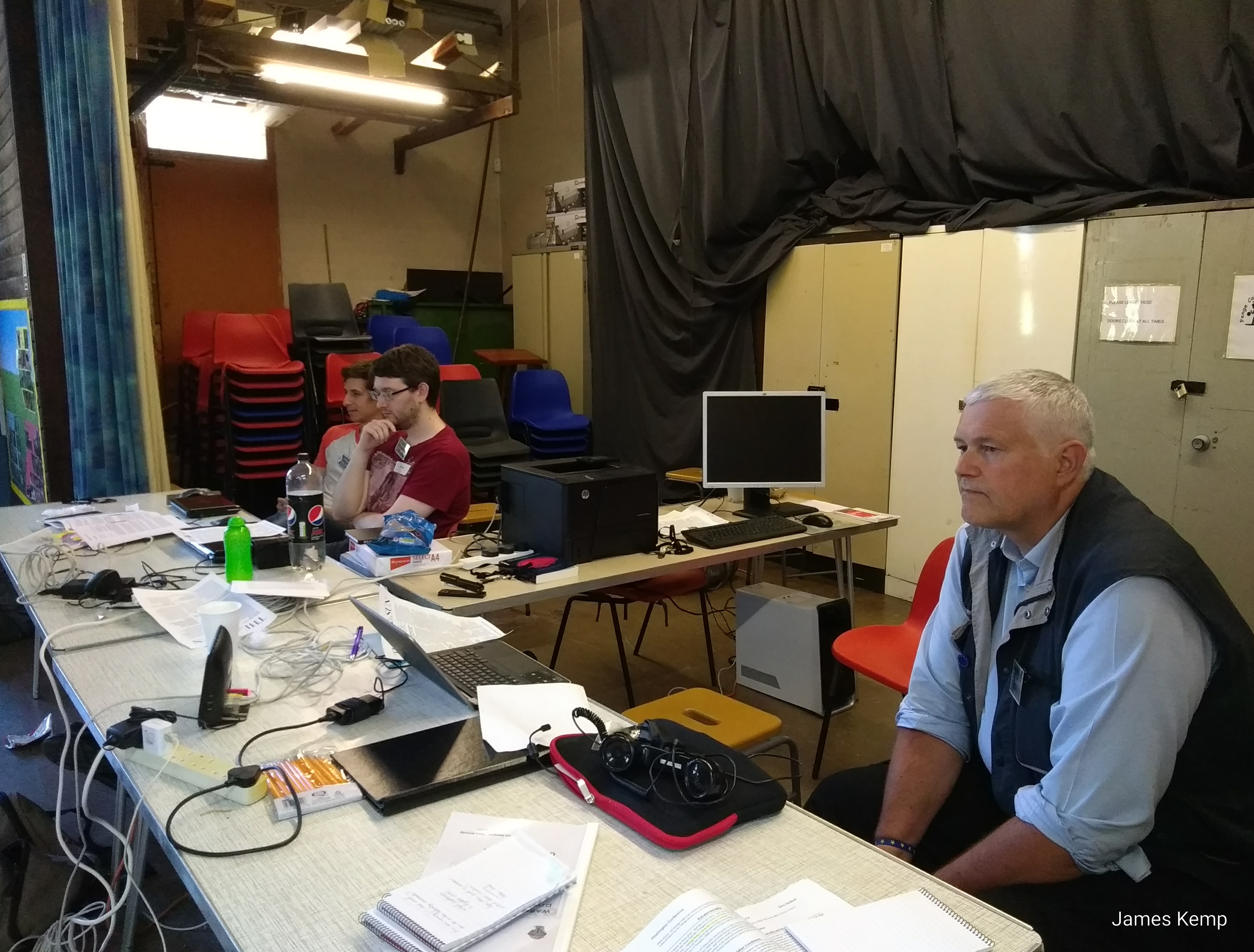

Watch the Skies 3

Last Saturday I was control for East Asia for Watch the Skies 3. This picked up where Watch the Skies 2 left off, with some modifications to rules and briefings etc to make it flow much better. There were a number of obvious improvements, the media being a prime example. Media Coverage There were more journalists…