Category: Strategy

-

Army Education for Officers and Soldiers

Paul Barnes wrote an interesting post (The Drums of the Fore and Aft) on Army Education and the inherent problem in highly educated NCOs and Warrant Officers being over-ruled by inexperienced 22 year old Second Lieutenants. It made me think a bit about this, and the contrast with specialists in non-military organisations. So my military…

-

Intern the terrorist sympathisers now?

Over the last 48 hours I’ve seen a lot of people calling for us to just intern the terrorist sympathisers now. The knee jerk reaction followed the Manchester bombing and repeated after Saturday night’s drive by stabbings at London Bridge. The feeling was that if the security services knew who these people were they should…

-

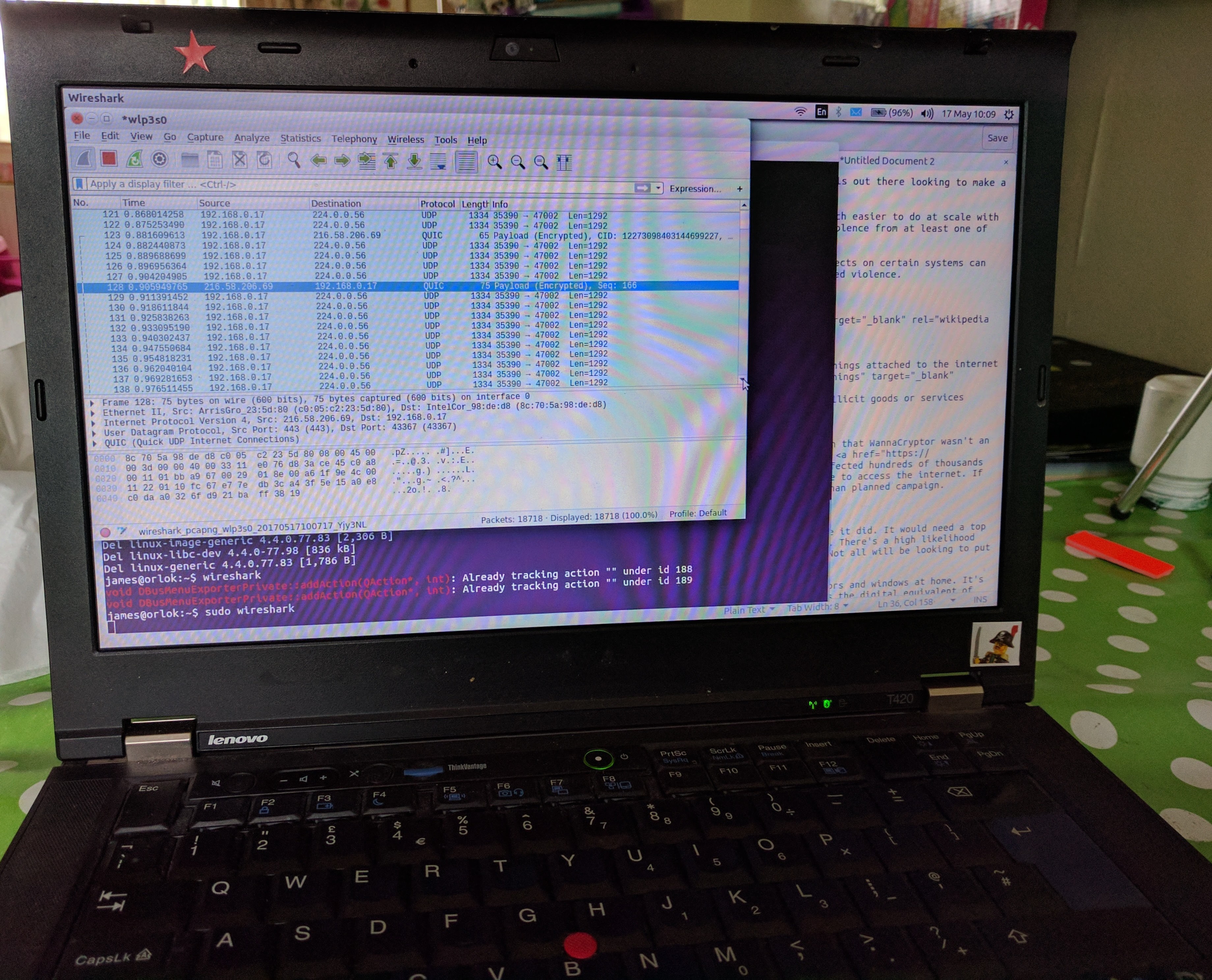

Cyber Warfare – Just a buzzword or scary reality?

Cyber warfare has been on my mind for a few weeks, even before the WannaCryptor incident. It’s been there because I’ve been looking at the innovation context for a digital service I’ve been designing as part of my T317 end of module project. That service is for government, and one of the risks is that…

-

Mass mobilisation for World War Three?

Mass mobilisation for a world war level conflict would need the country to repeat what it did for WW1 & WW2. Discussion I’ve read on twitter amongst those interested and knowledgable about defence (a mixture of serving officers, military historians and political observers) suggests that Britain has a real problem with the level of defence…

-

Objectives – Megagame advice

Objectives form the basis of game play in megagames. I’d like to start here by reminding you of three things: The British Army’s master principle of war; Selection and maintenance of the aim is the master principle of war Clausewitz‘s most cited quote; War is the continuation of politics by other means the British Olympic…

-

No Bombing Syria – it only helps ISIS

The UK Parliament has a vote this evening about bombing Syria. I’ve said before (On Syria, 2013) that I believe that bombing Syria would be a mistake. Here’s a summary of why it doesn’t help: No matter how careful we will kill civilians that we should be protecting It will cement the view that the West…

-

Watch the Skies 3

Last Saturday I was control for East Asia for Watch the Skies 3. This picked up where Watch the Skies 2 left off, with some modifications to rules and briefings etc to make it flow much better. There were a number of obvious improvements, the media being a prime example. Media Coverage There were more journalists…

-

World Building – Towns and Villages

One of the things that I often do when I am writing a story is to sketch a map of the area where the story takes place. This helps me to visualise what the characters will be able to see. The thing is though, you can’t just bang down stuff randomly (well you can, but…

-

Counterfeit Game Money

At Chestnut Lodge Wargames Group we design and play a lot of games involving game money. We do this to the extent that we often joke that all you need for a game are CLWG members and some (play) money. Â By definition none of this is real, but in game terms it is always genuine.…

-

Game Design Notes: World War One Strategic Battles

This was originally written as a game design session prompt for a session at Chestnut Lodge Wargames Group back in April 2004. A discussion thread on about this excellent blog post http://sketchinggamedesigns.blogspot.com.es/2014/01/the-wrinkles-of-tactics-first-world-war.html lead me to dig it out and post it here. World War One Strategic Battles Turn structure Three turns per year, March – June…

-

On Syria

The situation in Syria has caught public attention because of the alleged use of chemical weapons (most likely Sarin) by someone. I don’t usually stray into current affairs quite so much as this, these sort of situations are too raw to even think about designing games about them. However the press coverage seems to be…

-

CLWG July 2013 Game Reports

There were five of us at July’s CLWG meeting, myself, Nick, Mukul, Dave & John. There were three game sessions presented: I went first with a two part committee game called “The High Ground” about the consequences of cheaper surface to orbit space travel; Nick presented an economics card game for educating people about markets…