Hot Blood & Cold Steel: game design

-

Army Education for Officers and Soldiers

Paul Barnes wrote an interesting post (The Drums of the Fore and Aft) on Army Education and the inherent problem in highly educated NCOs and Warrant Officers being over-ruled by inexperienced 22 year old Second Lieutenants. It made me think a bit about this, and the contrast with specialists in non-military organisations. So my military…

-

Dunkirk – A different sort of war movie

I went to see Dunkirk with my 11 year old son last week. I’d read some reviews beforehand and chose the IMAX version. It’s an amazing movie that I think will bear watching again. I’ll try to avoid spoilers. Dunkirk The movie focuses on three stories, one on Land (over a week), one on the…

-

Intern the terrorist sympathisers now?

Over the last 48 hours I’ve seen a lot of people calling for us to just intern the terrorist sympathisers now. The knee jerk reaction followed the Manchester bombing and repeated after Saturday night’s drive by stabbings at London Bridge. The feeling was that if the security services knew who these people were they should…

-

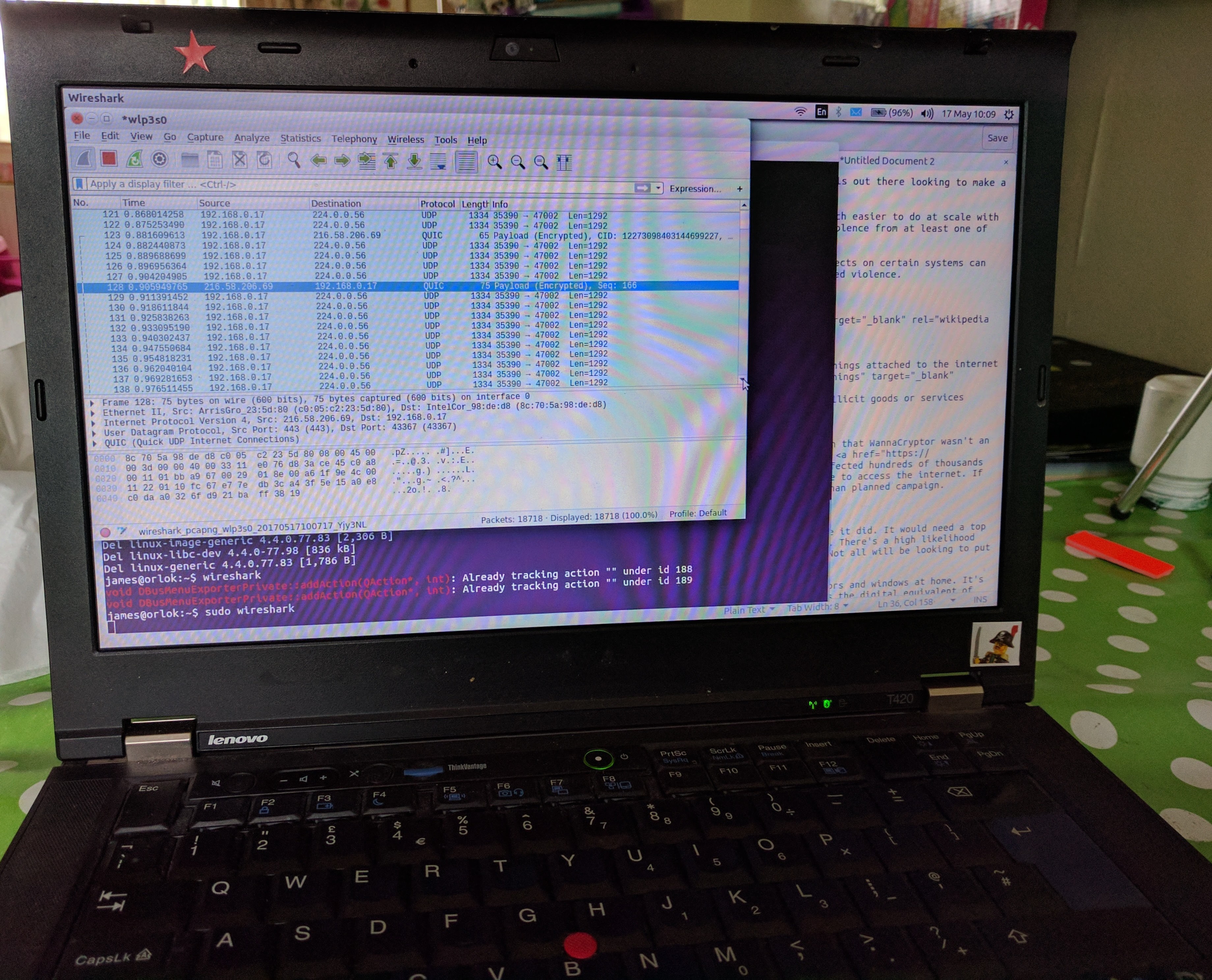

Cyber Warfare – Just a buzzword or scary reality?

Cyber warfare has been on my mind for a few weeks, even before the WannaCryptor incident. It’s been there because I’ve been looking at the innovation context for a digital service I’ve been designing as part of my T317 end of module project. That service is for government, and one of the risks is that…

-

Mass mobilisation for World War Three?

Mass mobilisation for a world war level conflict would need the country to repeat what it did for WW1 & WW2. Discussion I’ve read on twitter amongst those interested and knowledgable about defence (a mixture of serving officers, military historians and political observers) suggests that Britain has a real problem with the level of defence…

-

Leading Gurkhas – A Child At Arms by Patrick Davis [Book Review]

A Child at Arms by Patrick A. Davis My rating: 5 of 5 stars Davis became a Gurkha officers almost straight out of school in WW2. A Child At Arms should be on reading lists for junior officers and anyone involved in military policy. It compares well to Sydney Jary’s 18 Platoon, which was held…

-

![Dominion by C.J. Sansom [Book Review]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/350px-bundesarchiv_bild_183-h12751_godesberg_vorbereitung_munchener_abkommen.jpg)

Dominion by C.J. Sansom [Book Review]

Dominion by C.J. Sansom My rating: 4 of 5 stars I was recommended Dominion by a couple of friends after my review of the TV version of SS-GB. Dominion is a huge tome, it’s 700 pages long, and my first thought was that it probably needed some more editing. However I found it an easy…

-

SS-GB is Archer of the Yard a Collaborator?

Is Archer of the Yard just doing his civil police job or is he a Nazi collaborator? I have a fascination with the moral dilemma of being a collaborator or changing sides in civil wars and occupations. None more so than the situation that Archer of the Yard finds himself in with SS-GB. Let’s unpack…

-

![SS-GB [review] BBC Adaptation of Len Deighton’s SS-GB](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/SS-GB-image-Buck-Palace.jpg)

SS-GB [review] BBC Adaptation of Len Deighton’s SS-GB

I watched the BBC Adaptation of Len Deighton’s SS-GB last night. I read the book a long time ago, it was probably one of the first alternative histories that I ever read. I’ve also enjoyed Young Lions by Andrew Mackay which is also set post-German Invasion of Britain. SS-GB Review SS-GB has a lot of…

-

UNSOC Playtest After Action Report

UNSOC = Urban Nightmare: State of Chaos. UNSOC is Jim Wallman’s latest evolution of the megagame. After the 300 player Watch the Skies the next step was multiple simultaneous and linked megagames. I blogged about Urban Nightmare during its first run. I played as the emergency services with a friend. UNSOC is multiple cities in…

-

Logistics of Megagames

Amateurs talk tactics, professionals talk logistics Continuing the theme of advice for new megagamers I’m going to talk about the logistics of playing in Megagame Makers style megagame (like Watch the Skies). This is player logistics though, not in game logistics (see the military player advice for that). Logistics of Megagames Megagames are juggernauts. Once they…

-

Objectives – Megagame advice

Objectives form the basis of game play in megagames. I’d like to start here by reminding you of three things: The British Army’s master principle of war; Selection and maintenance of the aim is the master principle of war Clausewitz‘s most cited quote; War is the continuation of politics by other means the British Olympic…

Got any book recommendations?