Tag: British Army

-

![Destructive & Formidable by David Blackmore [Book Review]](https://www.cold-steel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/dsc_0068.jpg)

Destructive & Formidable by David Blackmore [Book Review]

Destructive and Formidable by David Blackmore is a quantitative look at British infantry doctrine using period sources from the British Civil Wars of the seventeenth century up to just before the Napoleonic wars. If anything you can see the constancy, which drove the success in battle of British forces, even when outnumbered. Development of British…

-

Army Education for Officers and Soldiers

Paul Barnes wrote an interesting post (The Drums of the Fore and Aft) on Army Education and the inherent problem in highly educated NCOs and Warrant Officers being over-ruled by inexperienced 22 year old Second Lieutenants. It made me think a bit about this, and the contrast with specialists in non-military organisations. So my military…

-

Mass mobilisation for World War Three?

Mass mobilisation for a world war level conflict would need the country to repeat what it did for WW1 & WW2. Discussion I’ve read on twitter amongst those interested and knowledgable about defence (a mixture of serving officers, military historians and political observers) suggests that Britain has a real problem with the level of defence…

-

Leading Gurkhas – A Child At Arms by Patrick Davis [Book Review]

A Child at Arms by Patrick A. Davis My rating: 5 of 5 stars Davis became a Gurkha officers almost straight out of school in WW2. A Child At Arms should be on reading lists for junior officers and anyone involved in military policy. It compares well to Sydney Jary’s 18 Platoon, which was held…

-

Objectives – Megagame advice

Objectives form the basis of game play in megagames. I’d like to start here by reminding you of three things: The British Army’s master principle of war; Selection and maintenance of the aim is the master principle of war Clausewitz‘s most cited quote; War is the continuation of politics by other means the British Olympic…

-

Soldier in the Sun (BBC 1964)

Soldier in the Sun is a newsreel type production of the British Army in the Radfan in Aden in 1964. Shot completely on location in Aden and featuring real soldiers talking unscripted about their experiences. I caught Soldier in the Sun on the BBC iplayer where it is still available more or less indefinitely. If…

-

OR Driven Wargame Rules

I’ve been tinkering with a set of small unit wargame rules informed by operational research rather than fashions in wargaming for a couple of years. The crux of these rules is the morale mechanism.  These haven’t quite got as far as I would have liked as I’ve not really had any time to complete or playtest…

-

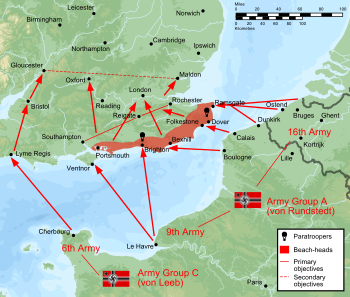

Could there have been a German Invasion of Britain in 1940?

Next week’s megagame Don’t Panic is an alternative history megagame about the German Invasion of Britain in 1940. It’s a popular what if and makes an interesting game for us British because the playing area is familiar to us from our everyday lives. At least it is familiar if you live in the South East.…

-

Operation Sealion: A Military Appreciation

The next megagame I’m going to is Don’t Panic a what if scenario on Operation Sealion, the planned German invasion of Britain in the autumn of 1940. I’m going to be the British Control. So no playing for me. However that doesn’t mean that I can’t look at how I would plan the Operation Sealion…

-

L/Cpl William Kemp – Killed in Action

Lance Corporal William Kemp of the 2nd Scottish Rifles was killed in action one hundred years ago. I grew up seeing his name on the local war memorial, as did my father who was also named William Kemp. My dad was keen on family history, he could tell me all the living relatives and knew…

-

Remembrance Challenge

We took our cubs to the local war memorial in the Church just down the road from the Scout Hall. Before we went we”d got the cubs to make a wreath of poppies and to write a message on it. Each boy did his own personal wreath. We then went on a walk down the…

-

Megagame: Iron Dice – Turn 10

Third week of October 1914 BEF Report to the War Office The Belgians on our left were attacked and driven out of their trench line, and retreated towards Calais. The BEF left flank is, although entrenched, hanging in the air again. BEF reserve troops are at St. Omer. A request to the navy is made…